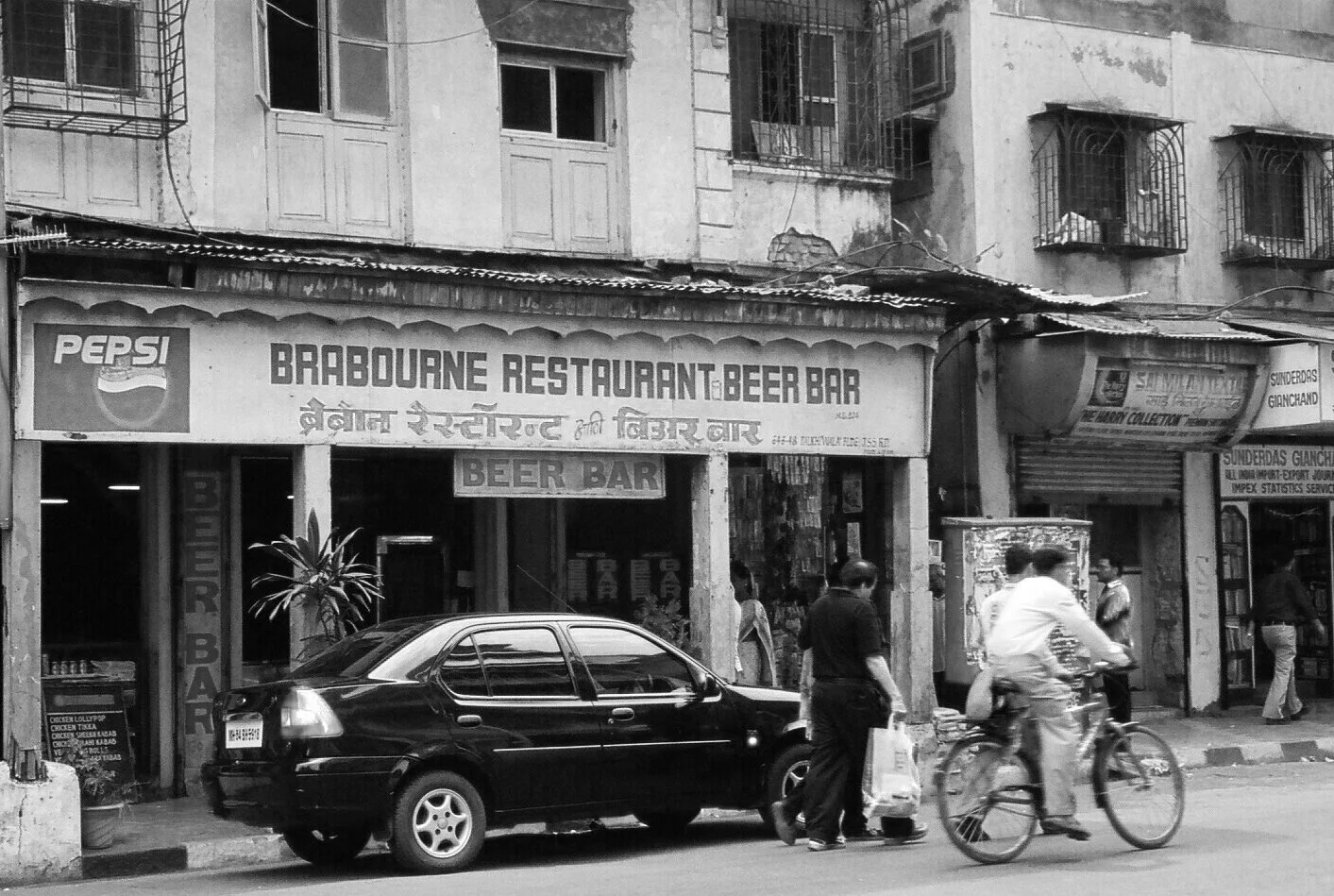

Brabourne Restaurant

{Dhobi Talao, Est. 1936}

They contributed in their own little way to the growth of Bombay, a city which has completely changed character.

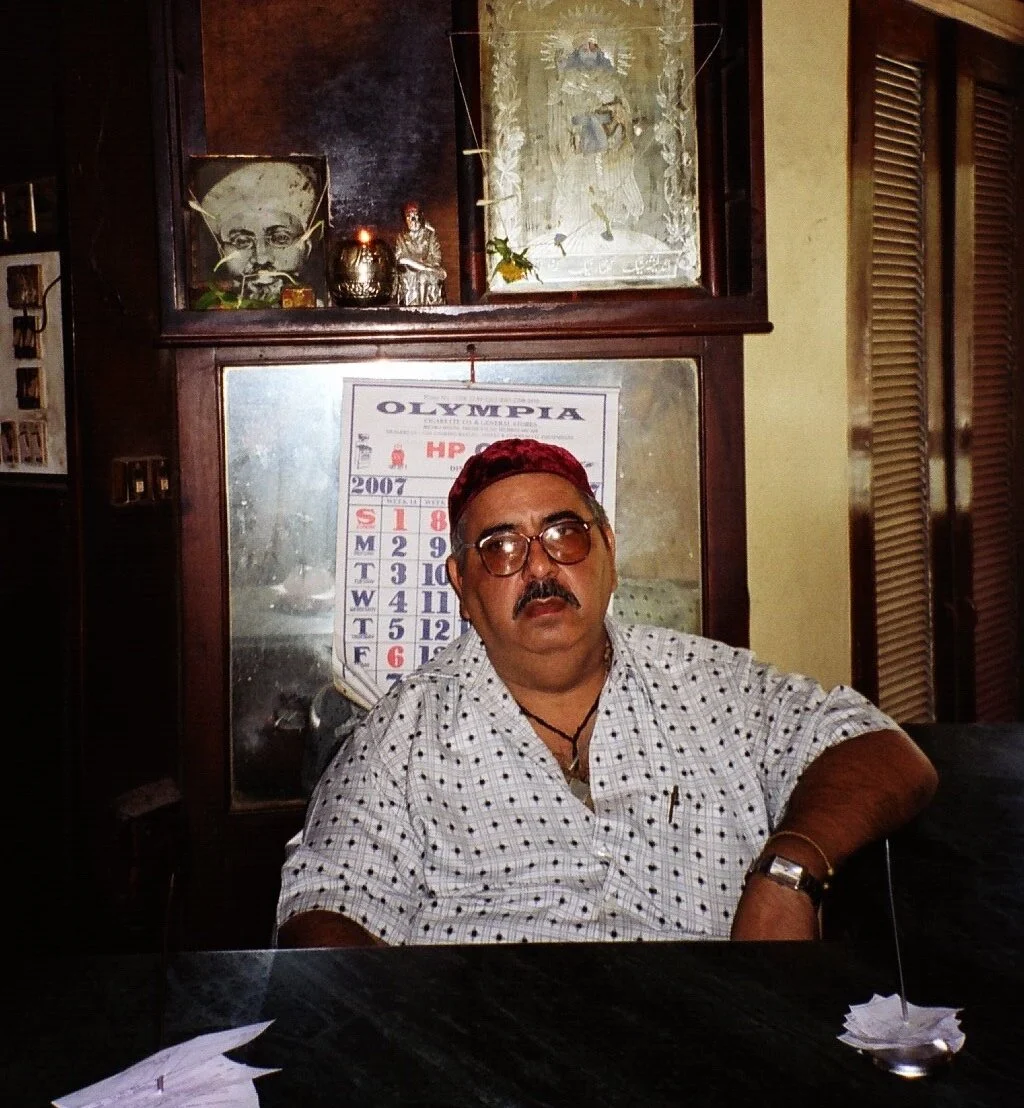

-RASHID IRANI, April 20, 2007

_______________________________________

My name is Rashid Irani, though our family name is actually Bahmani. But a lot of Iranis in Bombay have kept, and I am one of them, the surname Irani. Actually, I only found out I had a family surname when I tried to get an Iranian passport. Til then I didn’t even know that I had another surname. I always thought it was just Irani. Funny, really.

My very first years, maybe four or five years, my parents used to live in kind of sprawling chawl, which is a huge kind of, you know, a number of flats, a number of families occupying those flats, and this was at Fort Market, very close to Flora Fountain. It was predominantly Parsi and Catholic at that point of time. Later, we moved over here to Dhobi Talao.

Dhobi Talao was mainly Catholic and Zoroastrian then; Catholics for the reason that in those days Goa was not connected by air from Bombay, and the majority of the Goans were, and still are, employed on ships, in all categories, so whenever they would sign off from a ship they would land up in Dhobi Talao, and this was the place where there were various Goan clubs- living quarters with one huge room where a lot of people slept. What would happen is the moment they would sign off the ship they would temporarily stay here til they made arrangements to go to Goa. And of course at that time there were plenty of Zoroastrians - Parsis and Iranis - living around here too.

My father Rustom Aspandiar Bahmani emigrated from Iran in the late 1920s and like most Zoroastrian Iranians who came to Bombay at that time he came from the main centre, being Yazd, villages in and around Yazd. It was quite an arduous journey coming to India via Pakistan, and they got into a few difficulties along the way, but finally made it to Bombay and they started these restaurants, these tea shops and provision stores, and they succeeded in business beyond, I am sure, their wildest ambitions. Brabourne opened in about 1932, and my father started working here in 1934. The place was originally a stable for horses.

I'd say Iranis did well because they had the knack of melding into the surroundings quite comfortably, I guess because of the shop. I think that is one of the best things about running a business like this - you come into contact with a wide spectrum of people on a daily basis, so you have to, per se, interact with them, otherwise you'd have no hope of succeeding! The Iranis of course they were very, very hard working, and despite not having education in the formal sense, they had tremendous business acumen;they were hard working and practical, despite the fact that we'd get called junglees - which basically means rough, stupid, idiots. I sometimes feel Iranis get tired of being seen that way, it's so inaccurate.

A really vivid memory for me goes back to my days at St Xaviers - the local Jesuit school, and I had this teacher, I still remember his name, he was fearsome, but he was also, well, I actually grew fond of him, and one day, the very first day of class, when he was reading out the roll, he came to my name, stopped, looked up and asked me ‘what do your parents do?’ so I said “my father runs a tea shop”.

From that time on, he would invariably in class refer to me as ‘chaiwalla’ – a chaiwalla being someone who makes and sells tea. You know, at first I was really riled, especially since some of the other students, I mean my class mates also, started teasing me and continued to call me ‘chaiwalla’. I was angry at him, and since he was the teacher I couldn’t do anything. It was only much later that I realised this was his way of addressing all Iranis; a couple of my Irani friends who were one year senior said ‘why are you getting so upset?'

But I just didn't understand why it was so funny to be a chaiwalla's son, for Iranis like my parents slogged all their lives. The shop was their be all and end all – they would spend maybe 16 to 18 hours, 7 days a week, 365 days a year at work, but one of the things of course happening in those days was that each of these restaurants, they were rarely singularly owned, there were no single proprietors; there would normally be a partnership between 3 Iranians, or more.

Which meant that once a year maybe, or once every two years, one of the partners would take a long break – an extended vacation of a month, or two months. My father and mother invariably took my three brothers and myself for a holiday during our school vacation, mainly to this lovely place called Devlali which is an army cantonment about four hours away, and I have very, very fond memories of that place - for it was at a little cinema there called the Cathay I first fell in love with film.

I think what distinguished these Irani cafes was you could sit on a table with just one cup of tea and read the newspaper for hours on end, and you could be sure that you would never be asked to leave – that was one of the great things, so they became a kind of meeting point for a lot of people - there'd be innocuous debates to the more kind of intellectual discourses, everything took place within the confines of the Irani café.

Brabourne for me is, I think, a great institution. It has in its own way, and going back to the chaiwalla thing, you know one of the things I always feel, is that I am grateful for my father and his partners who started this place, for contributing, if only as chaiwallas, to the city. It is amazing that they contributed in their own little way to the growth of Bombay, a city which has completely changed character; it really no longer exists as it once did.

Today Dhobi Talao is increasingly a commercial hub. Earlier it was predominantly a residential area, today it is commercial. Within a decade I can see a whole slew of malls dotting the skyline around here. We are next in line, I suppose.

__

From an interview with RASHID IRANI, April 20, 2007

BRABOURNE CLOSED AFTER 76 YEARS ON APRIL 26, 2008

ca. 1990

2008

1984

ca. 1939

2007

2007

2007

___________________________________

IMAGES: top to bottom:

RASHID IRANI, BRABOURNE RESTAURANT, Dhobi Talao, ca. 1990, photographer Raghubir Singh, copyright Raghubir Singh

BRABOURNE RESTAURANT, Dhobi Talao, 2008

BRABOURNE RESTAURANT, Dhobi Talao, 1984, photographer Sooni Taraporevala, copyright Sooni Taraporevala

ADVERTISEMENT for BRABOURNE RESTAURANT from Hormusji Dhunjishaw Darukhanawala, Parsi Lustre on Indian Soil, published by Claridge, Bombay, 1939

BRABOURNE RESTAURANT, Dhobi Talao, 2007, photographer Rafeeq Ellias, copyright Rafeeq Ellias

BRABOURNE RESTAURANT, Dhobi Talao, 2007, photographer Rafeeq Ellias, copyright Rafeeq Ellias

______________________

Kyani & Co.

{Dhobi Talao, Est.1904}

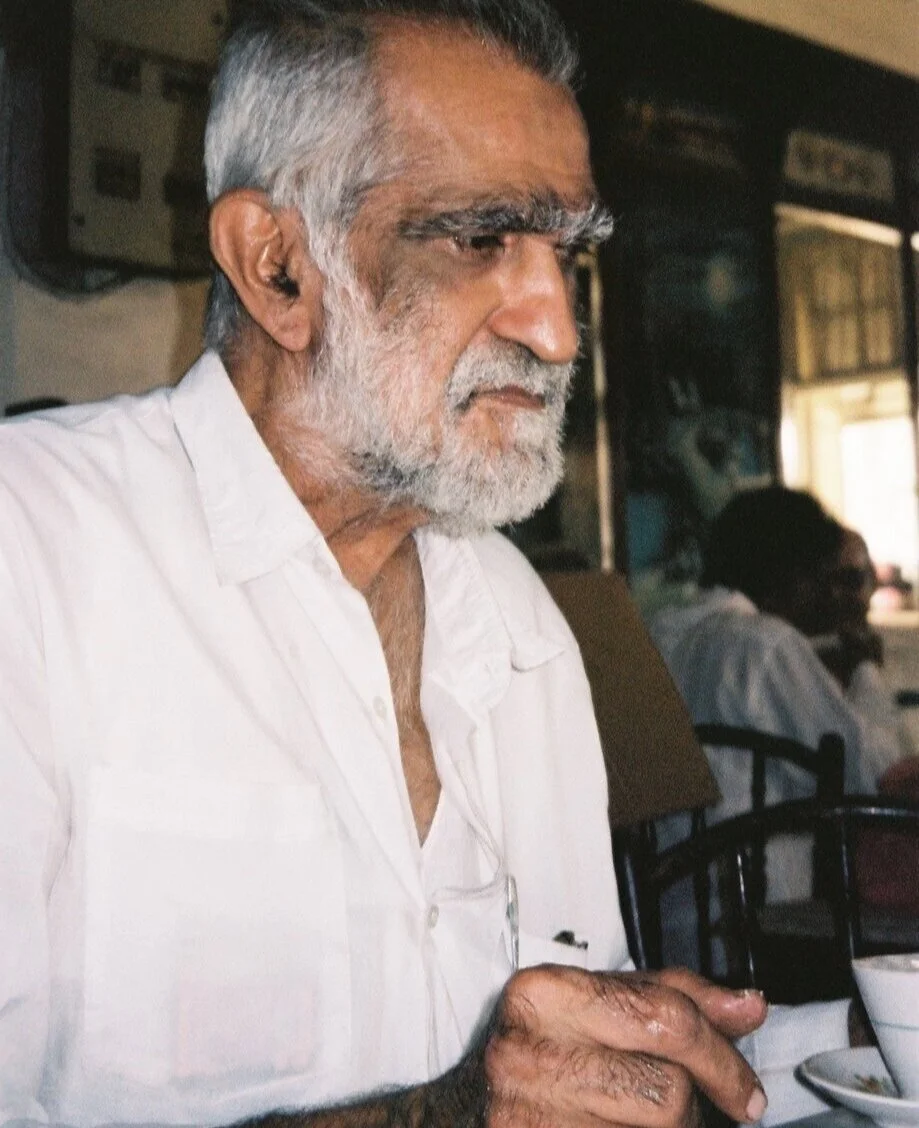

Kyani is now 103 years old, we are supposed to be the oldest Irani café still operating. We had to make my sons Farookh and Farad partners in the business; I am old now, any moment I may leave to go.

-Aflatoon Khodadad Shokriye, April 2007

______________________

My name is Aflatoon Khodadad Shokriye. Khodadad is my fathers name, Shokriye is our family name. Aflatoon Khodadad Shokriye. I came to Bombay from the city of Yazd in Iran in 1948. My father was here, he sent me a visa, student visa to study here. At that time I was 18 years old.

The trip was during monsoon, up to Quetta it was OK- we went from Yazd to Kerman, Kerman to Zahedan, Zahedan to Quetta. From Quetta again we came to Karachi, from Karachi we came by steamer to Mumbai. I was along with some three, four people from Yazd. One was aged like my father, and he was our neighbour in Yazd, his son was there and another fellow was there of my age. It was a journey I will never forget. Ever. More than one week of travelling.

So it was monsoon, and in Bombay it was raining, and raining, so many things which I was not used to! Day and night it was raining. That is why I was repenting! And the food! Indian food it is, what you call, hot food. But in our own restaurants we used to make the Iranian type of food.

When I arrived in Bombay I was repenting why I came - the Britishers had left and even at that time the hygienic conditions were not good. I thought Iran was better. I was new, I did not know language, no friends and all so I did not like it. Slowly, slowly I changed. The local people were friendly, good people. When they knew that I did not know the language, they used to talk more to me, and I picked up the language.

My father was here at Kyani, my son is the third generation that are running this restaurant, so this is a kind of family restaurant, established 1904 by my father Khodadad and his brother Khodamorad. Here then it was all Iranis working here. It was an institution, like Iranis, what you call it, it was like a training college!;they used to come and learn business, how to prepare, how to do business, and other things, and they used to go and make partnership with others and start their own business, set up their own Irani café. In 1948 in Dhobi Talao Parsis were everywhere, Parsis and Christians. But, uh, slowly, slowly Parsis have migrated out of India, many of them died, many of them they did not get married, the population came down.

My father told me that the Iranis when they came here, they were working in the Parsi's houses, they were employed and worked in there, and uh, in the morning they used to meet, they would gather and discuss about life and things, so one fellow started preparing tea for the rest, but he used to charge them. So the idea of making tea came to the mind of the Iranis, so they started this tea business and all. By 1948, when I arrived, at every junction almost there was an Irani. They all selected those junctions, those street corners. Because the junctions are one, two, three sides of the road. Anything that was available they used to take.

Today our customers are a cosmopolitan mix - all types of people. Formerly it was mainly Christians and Parsis, the majority. But now, it is cosmopolitan. You cannot stop anybody entering your restaurant. It is a rule of the government, law. In those days you see, the customer was a different type of culture. Tie, coat and all. Hindus of high standard also used to come here. But majority were Parsis and Christians. In years past Bombay was very safe and we used stop sometimes at 12 o’clock (midnight), but slowly, slowly we have reduced. Because at night people are in a different category in Bombay, they are different. People sometimes make trouble at night. So now we are closing it at 9 o’clock.

I think our regulars appreciate that we have stayed open, offering this type of service- we get people coming who were our customers some ten years back, fifteen years back, they have gone to America, or UK, Canada, then ten years later they come to Kyani, and they are so happy to see us, that we have maintained the same type of restaurant. I tell you, one year I went to America - there was a gathering - all Parsis, Iranis, and as soon as they saw me they said “ohh, Kyani, he has come from Kyani in Bombay”. I couldn’t believe it. Incredible how many people remembered Kyani.

Changes? In about 1952 an Irani had a café, and this man used to put kus-kus (poppy) in the tea. And believe it or not, the taxiwallahs who were running the taxi, they used to go there and take their tea always, otherwise they were not happy with their tea. Then one by one, all the cafes started kus-kus tea, we had it here at Kyani, finally the Municipality came to know about it and they stopped it. It is prohibited. The Municipality will take your license and you have to go behind the bar if you tried that now. When Britishers were here, they were foreigners, we Iranis were also foreigners, we got friendly treatment when we went to the government departments; they knew that we were new here, we were also foreigners, so they said “you have to stop putting that in the tea”, and we did.

In the past, people from offices, from Fountain, from Colaba, they used to come to Dhobi Talao, because there were two big shops selling confectionary – Bastani and Kyani - across the road from each other. Now there is only Kyani, so they go wherever they like to buy their requirements. Bastani closing has affected our business, you see. The nature of the business at Bastani was the same as Kyani. When it was there it was better. The movement of the people is now restricted. When Bastani was still there lots of people used to come from outside – they would maybe buy their sweets at one place, and just walk across the road and have their tea at the other.

__

From an interview with Aflatoon Shokriye, Dhobi Talao, Mumbai, April 2007.

Aflatoon Skokriye expired in Mumbai in December, 2015.

ca 1940

ca 1980

2010

ca 1980

2020

2008

![KYANI2[1].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fcdc5e73b4ad40d4a7d6900/1608103657270-GXZW7JY9GV5SH3N4C8LW/KYANI2%5B1%5D.jpg)

2006

__________________________

IMAGES: top to bottom:

AFLATOON KHODADAD SHOKRIYE, KYANI, Dhobi Talao, 2008, photographer Rafeeq Ellias, copyright Rafeeq Ellias

PASSENGER DOCKS, Karachi, ca. 1940, British Library collection, photo 425/(5)

KYANI, Dhobi Talao, ca. 1980, photographer Mahendra Sinh, copyright Mahendra Sinh

KYANI, 2010, photographer Charles Victor, copyright Charles Victor

KYANI, Dhobi Talao, ca 1980, photographer Mahendra Sinh, copyright Mahendra Sinh

KYANI, Dhobi Talao, photographer Bruce Carter, copyright Bruce Carter

Interior, KYANI, Dhobi Talao, photographer Barath Ramarutham, copyright Barath Ramarutham

KYANI, Dhobi Talao, 2014, photographer Paul Williams, copyright Paul Williams

KYANI, Dhobi Talao, 2008, photographer Rafeeq Ellias, copyright Rafeeq Ellias

KYANI, 2006, photographer Bruce Carter, copyright Bruce Carter

Exterior, BASTANI & CO., Dhobi Talao, ca. 1995, photographer Barath Ramarutham, copyright Barath Ramarutham

Sassanian Bakery and Restaurant

{Marine Lines, Est. 1913}

As I take care of my wife, I take care of my place also. I love this place, this place is just like a temple to me.

-Meheraban Kola, April 2007

_________________________________

My father was from a village called Arestan. In Iran. My mother was also from Arestan. My fathers father was an agriculturist…he used to grow fruits and other things – pomegranate, apples. My father arrived in Bombay in 1920. After the death of his mother, uh, he was sent to Bombay by father and then he started working in a restaurant.

First he worked in Goodman Restaurant which was an original Persian bakery which later on closed down and now there is a footwear shop over there. After that my father worked at Kyani, he started over there as a waiter, then he became a cashier over there, he has worked as a baker also over there; until 1945 he was working over there.

In 1947 he took up Sasanian which was started in 1913 by the Yazdabadi family, Mr Rustom K. Yazdabadi. He was the one who started Sasanian and I think so, but not sure, ahhh, in the end of the 1800s, Kyani had come up and that was started by his elder brother, Yazdabadi’s elder brother. And at first there was Kyani restaurant at the corner, then there was Brabourne Restaurant, which is still there, and in this lane, Second Marine Street, there was a Café Wellington which was an Irani restaurant in the late 1800s. This was, I think, the first Irani in Mumbai. It is not an Irani restaurant now.

They used to say “Bombay toh sonapur hai”– many people used to come from Iran for prosperity. They used to come on donkey’s back from Iran, half the way they used to come on donkey’s back*.

The high time of the Irani cafes were I think during the British rule. There were a lot of Irani cafes and at that time, even after that, still Udipi restaurants didn’t come (yet) to Mumbai. Irani restaurants were there, and the main reason Irani restaurants were on the corner of every street, and why the Irani restaurants were prosperous I can say, you see, an Irani restaurant, once it opened at 5 in the morning, it had the newspapers, people could read, papers used to come at that time, by 430, quarter to 5, and you could feel the warmness of the paper, that it had come directly from the press.

Another thing is, each and every Irani restaurant, though it gave tea, bun maska, omelette and some also had food a little bit, they had other necessities of life which people wanted - toothpaste, soap, hair oil, all the necessities, needs, even envelopes were kept. Even cigarettes were kept. Just like a small convenience store.

In the beginning, there was no food here, only bun maska, chai and omelette. Eating habits have changed in the city because, see, people are … every people has a want to change, they do not want to eat bread and butter every day , they want idli sambar, and to try other things, Chinese and all that. So after Irani cafes then (came) Udipi places, ahhh in 1990s Chinese food became popular, all these different foods started coming and all have stayed. But still people love Irani tea. And they love to come and eat bun maska, chai, some of the modern generation they love to come over here. In 2000 we changed the menu, and started serving Parsi and continental dishes. Our dhansak is probably the most dish.

See basically the principle of me and my dad is whatever you serve should be good, and should be value for money. Because in an Irani restaurant a poor person comes, a rich person comes, a middle class person comes. As I take care of my wife, I take care of my place also. I love this place, this place is just like a temple to me, where I serve people, and I would like to see my each and every customer happy with what they have eaten.

And one more thing. The fire in the bakery here has never stopped since 1913. Though the bakery was once repaired, still we kept the fire, as we Zoroastrians worship with fire, I think my success is due to that also. Because we believe (in fire) and that has helped us to prosper.

__

From an interview with Meheraban Khodadad Kola Dhobi Talao, Mumbai, April 2007

* Bombay toh sonapur hai - Bombay is the city of gold

ca. 1970

2007

ca 1940

ca 1986

2020

2020

2020

ca 1940

_____________________________________

IMAGES: top to bottom:

MEHERABAN (AKA MERWAN) KHODADAD KOLLA, Bombay, ca. 1970, courtesy Meheraban Kolla

MEHERABAN KHODADAD KOLLA, SASSANIAN, Marine Lines, 2007

K.R. SASANIAN advertisement, ca. 1940

SASSANIAN, Marine Lines, ca. 1986, photographer namas Bhojani, COPYRIGHT Namas Bhojani

MEHERABAN KOLLA AND DILNAZ SANJAN, SASSANIAN, 2020, photographer Bruce Carter, copyright Bruce Carter

SASSANIAN, Marine Lines, 2020

SASSANIAN, Marine Lines, 2020, photographer Anushka Gupta, copyright Anushka Gupta

K.R. SASANIAN, advertisement ca. 1940

Britannia & Co.

{Ballard Estate, Est. 1923}

Many cafes have closed; in the 40s, 50s and 60s we had about three to four hundred Irani restaurants, bakeries, stores in Bombay.

Boman Kohinoor, Britannia & Co, Ballard Estate

__________________________________

Britannia Café was established by my father Rashid in the year 1923 and it happened to be the birth year, the year, I was born in this year, now nearly 84 years. The Zoroastrians who remained in Iran were under attack, so they had to carry on their life in villages, and most of them became farmers, and, uh, slowly there came to be short supply of water, actually they came from Yazd, my family. And Yazd was…water was very hard to get. Slowly there was no rainfall, and the water they were getting from the mountains also was drying up. So, they abandoned the villages and go for greener pastures.

So, the Parsis of India, they told the Zoroastrians of Iran if they would come to Mumbai, to Bombay, they would support them and that is why they came to India. Not being educated my father could not do any other work except the Parsis told him to start with some tea business, to prepare and serve tea, and uh, the Parsis helped them in the business and slowly they prospered. Actually, they gave them help to set up their stalls, and slowly the stalls gave way to small cafes, and then to restaurants and bakeries.

The Parsis had come 1075 years ago, and they had adopted the Indian culture, and they were very loyal to the British when they were here during the time of Raj. The Parsis of India, they mixed with the Indians and during British time they attended schools, got educated, they became engineers, lawyers, but the Iranis coming later did not get themselves educated, but they adopted this Parsi culture because our religion is same.

Parsis, originally, they themselves being very cultured, they mixed with the British people, very well, the British also gave them support and help. Well, the British did that maybe for a political purpose, they did so because they themselves were foreigners here, they could mix better with the Parsis than with some of the Indians.

Many cafes have closed; in the 40s, 50s and 60s we had about three to four hundred Irani restaurants, bakeries, stores in Bombay, but slowly they are diminishing, and now they are on the verge of vanishing. I think only about twenty, thirty Irani restaurants are left today.

Eating habits have changed, in the sense that formerly in the British time our restaurant was serving continental type food, bland food, and the Europeans and high society type of people were not eating spicy food, but now, after independence, we had to change, we had to cook food according to Indian tastes – with spices, and masala and all those things. So, biriyani has become popular, pilau has become popular, and mutton, and gravy, gravy cutlets have become more popular than during the past. We used to have beef steak, what they call chops, fish and chips, all those things, but now they are not a part of our menu at all.

Gandhiji came in power and he became a political father figure of India, then they brought about independence, he said all of us are children of God, why should there be this difference? All restaurants to be open for all castes and communities. That forced us to put up a board, saying there was no restriction for any caste or colour.

When Iranis started coming to India, especially to Mumbai, there were a lot of vacant premises, and most of the corner premises were vacant, this may be superstitious, but the Hindus would not take the corner, saying that it was very unlucky for them, so the Iranis were coming, and they would find the corners better for business, and so they started renting them. My grandfather started Kohinoor Restaurant, just near Bombay GPO. It was one of the first Irani restaurants in the city, about 1890,'95, around that time.

__

From an interview with Boman Kohinoor, Ballard Estate, Mumbai, April 2007

Boman Kohinoor expired in Mumbai in September, 2019.

Download an interview transcript

2007

2015

2016

2016

2016

2007

2014

2007

_____________________________________

IMAGES: top to bottom:

BOMAN KOHINOOR WITH SONS AFSHIN, left, and ROMIN, right. A portrait of Boman's father RASHID hangs above, 2007, photographer Bruce Carter, copyright Bruce Carter

BRITANNIA, Ballard Estate, 2015, photographer Ivo Daskalov, copyright Ivo Daskalov

BRITANNIA, Ballard Estate, 2016, photographer Mamiko Oka, copyright Mamiko Oka

BOMAN KOHINOOR, BRITANNIA, Ballard Estate, 2016, photographer Premshree Pillai, copyright Premshree Pillai

BRITANNIA, Ballard Estate, 2016, photographer Mamiko Oka, copyright Mamiko Oka

BRITANNIA & Co., Ballard Estate, 2007, photographer Bruce Carter, copyright Bruce Carter

BRITANNIA, Ballard Estate, 2014, photographer Clay Hensley, copyright Clay Hensley

KOHINOOOR RESTAURANT, Fort, 2007, photographer Bruce Carter, copyright Bruce Carter

Cosmopolitan Restaurant and Stores

{Prathana Samaj, Est.1932}

The success of these places, on the street corners? Look, Iranis mostly, in the old times, they did not care what the Indian people said about them - they do what they had to do.

Rustom F Irani, November 2007

_____________________________________

My father Khodabux Merwan Irani came to Bombay in about 1920, he was 18. When he came to India, not a single word of Hindi did he know, but still he learnt Hindi, Gujarati, everything, on his own. He had a very tough, tough, tough time. They were from Iran - Kerman, near Kerman, a small place called Jupar. They were farmers -wheat, and we had an orchard also, and in that orchard was watermelon, pomegranate, apricots, and mulberry.

The very starting of the Cosmopolitan, it was I think in 1932, my father was running the Good Luck restaurant on what is V.P. Road now. He started at Café Cecil, another Irani café now gone. He asked them if he could work, for nothing, to get experience you see. He went to Café Cecil and said 'can I work over here?' First they said no, and he said 'I don't want anything from you, but let me work, let me learn something', so they allowed him to work.

I remember when we started making biscuits, about 1956, we had no experience whatsoever, for three months, believe me, we used to prepare biscuits, and they were like wood! We actually threw the first batches into the sea! But one day at closing time, 11o'clock at night, I said I must keep trying - I prepared khari biscuits, and by God's grace they started to turn out beautifully. So then we began doing cakes - plum cake, currant cake, I just taught myself! We still prepare Christmas cakes here in December, and people just love them.

The success of these places, on the street corners? Look, Iranis mostly, in the old times, they did not care what the Indian people said about them - they do what they had to do. For instance I will tell you, my great grandfather, he had a donkey, and that donkey wouldn't pass over the bridge. The river was full and there was too much water there and the donkey doesn't want to go because he is afraid, so my grandfather, he carried the donkey on his shoulders and passed across..that is what the mentality was..they always found a solution to any problem, and made things work. Resourceful people; very, very, very practical.

My wife Freny, by God's grace, she has helped so much with this business, especially since my father died in 1976. Her father was a baker, she knows hard work. We met in 1967, and married in 1969. Our son Humin was born in 1970. Today he works here also. I am Iranian, no doubt. I have an Indian passport, but I am Iranian, although really I am just a man living on the surface of this earth, and soon it could be time for me to make a move. In this area there was Yazdani Restaurant, Original Persian Restaurant, Hardings Restaurant and Stores, Café Shirin; they are all gone now. Original Persian had a very, very, very good name. We have lasted longer, but who knows for how long; I think the future for the Irani restaurants still left in Bombay is bleak.

__

From an interview with Rustom F Irani, Mumbai, November 2007

Rustom Farook Irani expired in Mumbai in 2013.

Listen to an audio excerpt

Download an interview transcript

_________________________________

IMAGES: top to bottom:

RUSTOM FAROOK IRANI, Mumbai, 2007, photographer Bruce Carter, copyright Bruce Carter

Advertisement featuring RUSTOM KHODABUX IRANI AND COSMOPOLITAN RESTAURANT AND STORES, ca. 1950

SHERYAR KAVYANI, ca. 1960

FRENY AND HUMIN IRANI, 2007, photographer Bruce Carter, copyright Bruce Carter

COSMOPOLITAN RESTAURANT AND STORES, Prathana Samaj, Mumbai, 2007, photographer Bruce Carter, copyright Bruce Carter

COSMOPOLITAN RESTAURANT AND STORES, Fatima Manzil, Raja Rammohan Roy Road, Prathana Samaj, Mumbai, 1989, photographer unknown, courtesy Sir H.N Reliance Hospital Foundation

COSMOPOLITAN RESTAURANT AND STORES, Prathana Samaj, Mumbai, 2007, photographer Bruce Carter, copyright Bruce Carter

RUSTOM F IRANI WITH SON HUMIN, right, and Irani tourist, ca. 1990

________________________

2007

ca. 1950

ca 1960

2007

2007

2007

1989

2007

ca. 1990

Café Universal

{Fort, Est.1921}

For those of us who have been able to change with the times, the future of our businesses is bright.

Gustad Dehmiri, April 2008

____________________________

My name is Gustad Dehmiri. I was born in Yazd, Iran in 1944. My fathers name was Framroze and my mothers name Keshwa, and we are four girls and two boys in our family. All of my sisters are living in Canada, one of my sisters was here, she has expired now.

I came to India 1985, my father was a partner in Leopold in Colaba for a long time. He was young when he start working in Leopold, maybe 20 years old. I still have a share in Leopold, and this place here, Café Universal I bought some time back. It was a simple beer bar and chai and bun maska place only. I renovated the place, totally changed it to beer bar and full restaurant.

The owner of Café Universal was Behram Radmanesh, today he is 75, 80 years old, all his family is in America, so he has gone, he go to the States and stay there, once a year he comes back here for a holiday, then goes back because nobody is here to look after him.

Leopold was started in 1871 – first it was a drug store, then it changed to a wine market, wine shop, then my father and my uncle started it for a restaurant about 100 years ago, in 1907 I think.

So Leopold’s was started by our family, my father, my wife’s father and two other partners – one by the name Rustam. And one by the name of Sheriar, they were co-partners, running that place, and now they expired, and today Sheriar’s sons Farhang and Farzadh and myself, my brother and my wife Thrity we are the partners of Leopold’s today. Farhang and Farzadh manage Leopold’s day to day though.

Leopold’s, like this place Café Universal, was just chai, bun maska – just a typical old Iranian restaurant. Yeah, that is the story of these old Iranian restaurants; chai, bun maska, khari biscuit, pattice and all that. After that when the beer was more freely available in Bombay people realised aelling beer is much better profit than selling just chai!

Leopold actually, the Leopold was the name of the King of Belgium, ok, the King of Belgium was named Leopold and from that, in the British time it is named by them, Leopold Restaurant, a lot of people liked royalty in those days! Times change.

So when I came to India in ’85, we changed the food, this, that and people started coming, as a tourist centre. Everybody coming from abroad directly from airport to Leopold and they know their friends are going to be there, and from that Leopold became well known. It is written the name of Leopold in guidebooks, the whole world, everywhere, in Canada, in US, India wherever you go you open the book and Leopold’s name is there, that’s why it became so famous.

Café Universal was old and run down by the time I bought it; they were a different kind of customer. They were working on the docks, most of them. But now these docks are closed here, they shut down. They went to New Bombay.

Iranis have been hardworking people, only the thing is that the young generation, they didn’t want to go after their fathers, like in restaurants, because they study so they say ‘why should I come and work in a chai restaurant with dad?’

They maybe wanted to change the model, change the design, because still you see there are a few of that old type of Irani restaurant, old chairs and tables, and I told some people “why are you not interested in remodelling the place?” They say ‘no, if we make better the tax man will come and say “oh, from where have you got this money?”’

But for those of us who have been able to change with the times, the future of our businesses is bright.

__

From an interview with Gustad and Thrity Dehmiri, Mumbai, April 2008

______________________

IMAGES, top to bottom:

GUSTAD AND THRITY DEHMIRI, Mumbai, April 2008

GUSTAD DEHMIRI AND BEHRAM RADMANESH AT CAFE UNIVERSAL before renovations, ca. 2004

CAFE UNIVERSAL, 2009, photographer Dany Birchall, copyright Danny Birchall

Advertisement for LEOPOLD & CO., in Hormusji Dhunjishaw Darukhanawala, Parsi Lustre on Indian Soil, Claridge, Bombay, 1939

LEOPOLD'S, Colaba Causeway ca. 1990, photographer Brian J McMorrow, copyright Brian J McMorrow

CAFE UNIVERSAL, 2017, photographer Nicolas Mirguet, copyright Nicolas Mirguet

CAFE UNIVERSAL, 2009, photographer Anil Kalhan, copyright Anil Kalhan

CAFE UNIVERSAL, 2013, photographer Puku, copyright Puku

Leopold & Co.

{Colaba, est. as a café ca. 1890}

I think Daddy would be proud of us.

-FARZADH SHERIAR JAHANI, March 17, 2009

_______________________________

My name is Farzadh Sheriar Jahani. I was born in Bombay and grew up in Fountain. Flora Fountain area. That’s where, you know, most of the Parsis and Parsi communities were living back then. We lived in a five storey building, on one floor was an Iranian family that was living there, working for the Iranian consulate and there was a Punjabi living on the first floor. The rest of the flats were all occupied by Zoroastrians, Iranis.

My fathers name was Sheriar Framroze Jehani. My mothers name is Gulche Sheriar Jehani and they were both born in Iran. My father came down to India at the age of 15 or 16 with no money in his pocket. He had his brother and sister that he had to look after, and his parents. He was the oldest. So he had to come down to India to work, make a living and send some money back home for the family. They are from Yazd in Iran, actually just close by Yazd, a village called Taft.

My father got work in Irani restaurants, got the experience then like so many other Iranis, he took a share in several Irani joints. He ended up a partner in five restaurants in Bombay. One was called New York Restaurant which was on Hughes Road and he was a partner in Pyrkes Restaurant which was at Flora Fountain, he was a partner in Café Paris which was again at Flora Fountain. He was a partner in Moranaz and Company again very close to, ahhh, in the area of Fountain, and here at Leopold’s, that’s where my father was also. In fact, he was most of the time over here in Leopold’s and all the others were run by my father’s brother, his sister’s husband and other family.

Mr Rustom was a partner with my father here at Leopold’s and the building belonged to him. That’s why the building is called Rustom Manzil. Also Aspandiar Ferhandaz Irani was a partner, Sheriar Framroze Jehani was a partner and Framroze Irani was also a partner – he was Aspandiar’s brother. These were the four partners that were in Leopold’s. During that time it was only my father who was running the show. All the other partners were you know doing something else. Rustom was coming and going. Aspi had a travel agent called Asiatic Travel Service which was near VT station, right opposite New Empire Cinema. The other gentleman was Framroze, he was living in Iran. So it was left to my father to run it daily. And it was in 1980, in the 80s, early 80s that I was in the 8th gradeand I told my father I had an interest in learning the business.

It was more of an old type Irani café and store back then, they were selling confectionary items like…all kinds of things, they were selling biscuits and cakes and they were selling toothpaste, soaps, ah, you know medicines that didn’t require licences, such as Aspirin. They were selling cigarettes, cigars, and oh, um, khari biscuits and wafers and samosas and pattice and there were more sales of meals like English chicken roast and cutlet with soup, sandwiches, puddings and custards. There were a few Parsi dishes such as dhansak on the menu but not many. Today we have 140-odd items on our menu card. The changes came in the late 80s like in ’86, ’87 we introduced Chinese food into our restaurant, because we realised that people are now going for Chinese food and so we did too.

I remember my father telling me the 60s was the time of the hippies into the 70s, then the 80s was the time of the Arabs – the phases of Leopold I am talking about- then came the backpackers and now we have the expats. And a lot of Indians too as Indians have a lot more money these days than they used to.

When I was in my teens I used to meet people that were coming from Afghanistan, fleeing Afghanistan because the Russians had invaded. And we had a lot of, as I said, tourists, foreigners that were hanging around Colaba. So I have seen all kinds of crowd here. During the Iran-Iraq war we had people that had fled from Iran, young people that didn’t want to go to the war. I have seen people that were helping Iranians get out of the country illegally, but none of these transactions would take place in the premises for the respect of the owners, for the respect of the place and everybody had a good relationship.

And we had the Zoroastrian Parsis who would come here every Sunday morning, those were the cyclists. They used to have tournaments, races from Bombay to Pune and back, those kinds of things. There were a lot of young Parsis who would come basically on a Sunday – on a holiday. But not the rest of the week.

There used to be times when I would go with my Dad to Crawford market; because he would get up at 530 in the morning and by 6 o’clock he used to be in the market. At that time we had to go over there, we had to buy things like mutton, chicken, vegetables everything had to be hand picked and then we had a guy who used to be a cart-puller – he’d load onto the cart and deliver it to the restaurant over here.

My father used to have his Italian Fiat 1959 model which he used to get in and come back to Leopold’s in. Sometimes if his car was spoilt I might come with him and we would get a bus ride, early in the morning, on the BEST as we call them and I’d come with him, spend the day. Since my house was close – just 1, 2 kilometres from Leopold’s I could walk back home but no I would wait for my father , until he had finished, and then leave with him.

The world is different to what it was back then. People themselves have changed, those that wanted to move on in life have moved on in life. What we did was we moved with the times. Today my older brother Farhang and I manage Leopold’s. We have changed with the times and that’s why we have survived. I have seen so many an Irani joint either shut down, or sell out because they didn’t move with the times, they didn’t change.

I would say I am thankful to my Dad for having confidence in me and my brother, to let us make some changes while he was alive, while I was growing up still. He realised it was for the betterment of the business. You see people in those days – the elderly generation- were not having so much trust in their children, to let them bring in the changes. Have you heard about the crab in the basket? Sometimes I feel our community can be like that. If one is climbing up to get out of it, the other one is pulling that one down. Why? Success in a community should be accepted open heartedly. In fact, ask that person to guide you. Learn from that person. Educate yourself. Open your, your vision. Go and learn, don’t pull that person down.

I am really grateful to Gregory David Roberts for putting down what he had to in his book Shantaram. He himself is a great person. He has put us on the map of the world, it’s like ‘OK this is where Leopold’s is’. I have met so many foreign tourists, rich people who have read this book that would stay at Taj, came over here, and they say ‘we never thought of coming down to Bombay or to India or to Leopold, but after reading this book it pulled us to your place. And here we are eating, enjoying the food that’s been cooked here’.

The Iranis who started these places in Bombay, look, they have taken pain, they have sacrificed. Today I am sitting here, I have enjoyed, I have travelled, I have done all kinds of things my father didn’t do. My father and mother sacrificed so that I got this and I am enjoying this today because of their sacrifices. Today, I am not sacrificing in the same way to give life to my children, but I still protect them so that they get the best. Hard work and sacrifice is what they gave.

On 26/11/2008 two guys were standing by our door between 940 and 945pm talking on their cell phones. After that communication they were standing and talking to each other, maybe doing their prayers or what not and then one person, from his haversack, removes a hand grenade and hurls it into the restaurant. Soon after there was gun fire from an AK47. We lost several loyal staff and guests and others were injured. There was blood all over the place. It knocked all of us over.

It does not make any sense. Why kill innocent people? What have the people that you have killed done to anybody? They are sitting as human beings as you were once – they are no more human beings – eating their food with their family and friends. You have your differences with whoever, but why innocent people? I don’t understand. They basically came to kill foreigners. But we don’t let them win. We opened up after a few days and we stay open, we won’t let the fear and hate take over, we will work hard so that we then sleep. And time helps. I think my father would be proud of all of us.

___

From an interview with Farzadh Sheriar Jahani, Mumbai, March 17, 2009

2009

1932

1980s

ca. 2010

2015

2015

2009

2004

2009

2009

ca. 2000

2009

___________________________________________

IMAGES top to bottom :

Farzadh S. Jahani, Leopold’s Mumbai , 2009. Photographer Bruce Carter, copyright Bruce Carter

Advertisement for Leopold & Co., in Hormusji Dhunjishaw Darukhanawala,

Parsi Lustre on Indian Soil, Claridge, Bombay, 1939

Leopold's Colaba Causeway 1980s, photographer Marellaluca, copyright Marellaluca

Leopold’s, ca. 2010, photographer Thi Ho, copyright Thi Ho

Leopold Cafe and Bar, Mumbai, 2015, artist Somali Roy, copyright Somali Roy

Leopold Cafe and Bar, Mumbai, 2015, artist Somali Roy, copyright Somali Roy

Wall mural, Leopold’s Mumbai, 2009, artist unknown, photographer Bruce Carter, copyright Bruce Carter

Man smoking at Leopold's 2004, photographer Apoorva Guptay, copyright Apoorva Guptay

Night scene, Leopold’s Colaba, Mumbai, photographer Myke Fitz, copyright Myke Fitz

Leoopold’s Colaba, Mumbai, photographer Anurag Davare, copyright Anurag Davare

Cover, Shantaram, Gregory David Roberts

Wall mural remembering 26/11 Mumbai bombings, Mumbai 2009, photographer unknown

Farhang Jahani, partner, Leopold's Cafe 2009, photographer Jason Motlagh, copyright Jason Motlagh

Leopold’s Colaba causeway, Mumbai, ca 2000, photographer John Catnach, copyright John Catnach

Leopold’s Mumbai, 2009, photographer Bruce Carter, copyright Bruce Carter

B Merwan & Co.

{Grant Road, Est. 1914}

Many of the Irani places have changed now, they have become Chinese or pizza or beer bars. I wouldn't like that! No, I wouldn't like it, the old is gold.

-Boman Nasrabadi, April 2007.

_______________________________________

My grandfather came over from Iran. From Nazarabad. His name was Boman Merwan Nazarabadi. B. Merwan. As far as I know they could get a better life over here so they came from Iran and started these places. There was nothing like that in Bombay then my grandfather told me – no places to buy quick snacks and everything.

This area, this place around here, has grown like anything because the trains come here, and people come from all over, from suburbs, from Virar, Andheri, Borivali so when they came down they want something fast so first they come over here and get a chai or a mava cake or both!

Here is the perfect location next to Grant Road Station, it was my grandfather’s intuition or whatever you want to call it and you know, in Bombay, people have come from Maharastra, from all over, they used to come from many, many different parts of the country, but there was not so much population at that time that my grandfather first started out.

I started here in 1951 after I left college in Pune. My brother Soroush has been working with me for many years also. We are the third generation. Many of the Irani places have changed now, they have become Chinese or pizza or beer bars. I wouldn't like that! No, I wouldn't like it, the old is gold.

—

From an interview with Boman Nasrabadi, Mumbai, April 2007.

In 2014 Boman and Soroush Nazrabadi shuttered the doors and windows of Grant Road's landmark B. Merwan cafe for what many thought was the last time, 100 years after their grandfather Boman Merwan opened them up. But the closure wasn’t for long, and they reopened again a few weeks later.

___________________________________________

IMAGES :

B Merwan, grant road ca. 1915, photographer unknown

B Merwan ca 1975, ca. 1980, photographer Mahendra Sinh, copyright Mahendra Sinh

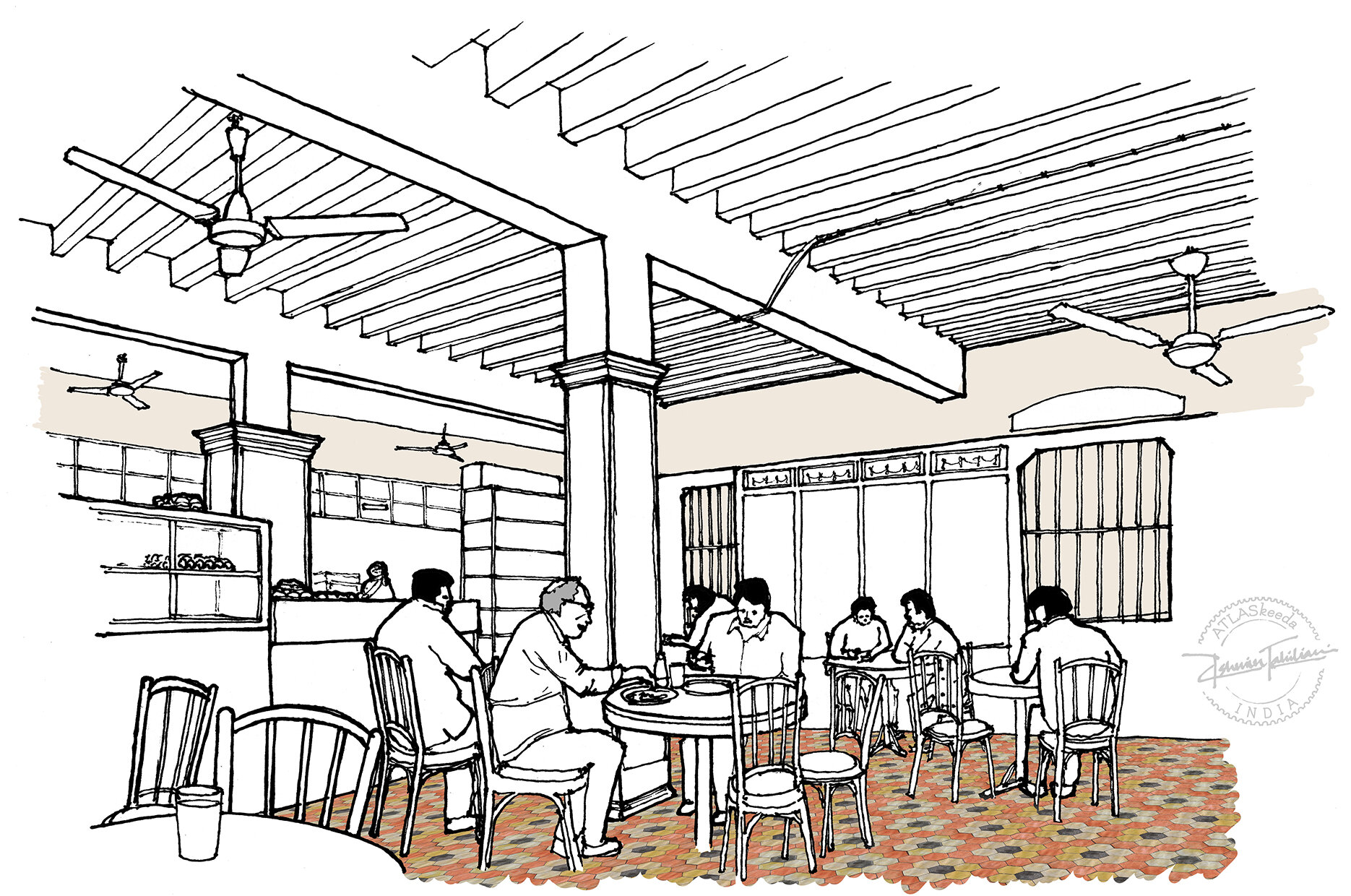

B. Merwan exterior 2021, artist Ashwin Tahiliani, copyright ATLASkeeda

B Merwan Interior 2021, artist Ashwin Tahiliani, copyright ATLASkeeda

B. Merwan, ca 2005, photographer Sue Darlow copyright estate of Sue Darlow

Soroush Nasrabadi, 2005, photographer Bruce Carte, copyright Bruce Carter

B. Merwan, ca. 1984, photographer Sooni Taraporevala, copyright Sooni Taraporevala

ca. 1915

ca. 1980

2021

2021

2005

2007

1984

_____________________________________

Atul Sabharwal's 2005 film Brun captures a day in the life of B. Merwan.

Yazdani Restaurant and Bakery

{Fort, Est. 1953}

In the old days Irani bakers used to slice the loaf by hand - now that’s an art!; to cut parallel slices in a uniform size.

Zend Meherwan Zend, 2005

________________________

Is there anything as delicious as a fresh, hard crusted gutlipao, perhaps, soaked in the gravy of a spicy curry? Gutlis, pao and a variety of other breads are made in large batches daily by the many bakeries scattered around Mumbai. These oven baked European breads made their appearance in Indian cuisine about three centuries ago. The very word pao, in fact, comes to us from the Portuguese, though there is a mistaken belief that the word derives from the feet (pao) that knead the dough!

To learn more, we sniffed the delectable aroma of fresh-baked bread that permeates Flora Fountain area and followed our noses till we reached Yazdani Bakery on Cowasji Patel Marg. We spent an enjoyable hour with the incredibly jovial Zend Merwan Zend, chatting about the history and traditions of bread in the city.

We learned that Zend’s grandfather, Zend Merwan Abadan, came to Bombay at the turn of the century and set up a bakery near the Alexander cinema. “My grandmother Jerbanoo would get up at 3 o’clock in the morning to knead the dough with the khamir”, recounts Zend. “Khamir is the basic yeast ferment and the technique was brought from Iran where bread was made by the sour dough process and not with readymade yeast as is done today; a lump of the dough would be kept for fermenting the next day’s dough. The Iranis and Parsees knew how to leaven dough but they learned the technique of pan bread from the Portuguese who also taught us the use of hops in baking”.

“They probably used hops in bread because it prevents unwanted bacteria from impregnating the dough and spoiling it”, Zend surmises. “Nowhere in Europe do they use hops for bread making, so I don’t know when and how they were introduced here. We had to boil two spoons of hops in water and we added it to the ferment when cool. When the bread was taken out of the oven, the whole area was filled with the sweet-sour smell of that bread which remained for days together without getting spoilt - it dried up but it was still edible.”

After his own father’s death, Zend’s father joined one of the oldest city bakeries at the age of eleven. This was the Rising Sun bakery at Golpitha presently owned by Shah Behram Sheriyar Irani. “They were famous”, says Zend. “Anton Pereira was their old Goan baker and they used to make seven-tiered cakes which were sent by P&O liners to Singapore and the Far East.”

“The bakery used to supply cakes and pastries from Colaba Military camp to Chembur Naka in a bullock cart. The bullock knew the journey so well that even if father fell asleep, the cart carried on and the bullock would stop near the shops where deliveries were to be made. My father knew each and every lane and all the bakers in Bombay. If the bullock collapsed, my father would pull the cart himself for some distance with the tired animal tied at the back!”

Today, at the bakery established by his father almost 50 years ago, Zend produces a wide variety of breads to cater to changing demands. The kneading process begins at 3 o’clock in the morning and the baking starts at 6 a.m. We sample some of his fresh, delicious and nutritious seven-grain bread, made from whole-wheat,barley maize, jowar,bajra, rye, andnachli or kang. He also bakes an array of cheese and garlic buns, chocolate bread, Swiss rolls, brown bread, whole-grain bread, pizza bread, sesame buns, hot dogs and of course, sliced sandwich bread and the ever-popular gutli and pao.

“The so-called ‘American’ bread that some people like these days contains at least five to seven different types of chemicals to make it soft and white and have a longer shelf life. How can you expect that bio-chemical mass to be digested by your system?”, he asks with disdain. “Bread must have a bite to it. In India we need bread which will maintain its structure when you dip it into gravies and sauces. Soft bread dipped in daal or tea would simply flop or disintegrate.”

We speak of flavour and aroma: “Because of the high demand for bread, modern bakeries do not ferment the dough by a bio-chemical process; the gluten matures with intense machinisation of the dough, whereas in our process of hand-kneading and slow machine kneading, the gluten takes at least 3 hours to mature and gets a chance of evolving alcohol and carbon dioxide, so the bread develops that typical sweet-sour flavour. Also, the skin of our bread is harder because we bake it for a longer time.”

Unsold bread at the end of the day is baked into toast. “The only people who appreciate this toast are Zoroastrian Iranis” says Zend with a smile. “During the days of persecution in Iran, they couldn’t afford to throw away anything and they broke up this dry noon (naan) or dry toast into small pieces, put them in a large bowl with salted curd, chopped onions and mint and pepper and it made a delicious breakfast. Today the toast is crumbled into papeta-ma-gosht and of course it’s excellent with tea.”

Sandwich bread: “In the old days Irani bakers used to slice the loaf by hand - that’s an art, to cut parallel slices in a uniform size.” Zend tells us about Kaikhushroo Irani of the Old Parisian Restaurant in Bruce Street who at the age of 65 can still expertly slice a loaf thinner than any machine. “He learned his trade at the age of 11 from Gustasp Irani of Naaz who introduced free-style wrestling to Bombay”.“Most people today want sandwich bread”, says Zend, “but they don’t realise that you can make excellent sandwiches out of pao; cut it along the equator, spread it with butter, a bit of cheese or ham, close it up and bake it again, and have it with a cold beer. It’s simply heaven on earth!”

By Sharada Dwivedi

This is an abridged version of an article originally published by Times of India, reproduced here in 2008 courtesy of Sharada Dwivedi.

Sadly, Sharada expired in 2012. She was a firm supporter of Irani Chai, Mumbai.

Zend Meherwan Zend expired in Mumbai in January, 2021

2011

2010

2010

2010

2021

2016

2021

2021

2006

________________

IMAGES, top to bottom:

Yazdani restaurant and Bakery, 2011, photographer Elroy Serrao, copyright Elroy Serrao

Zend Merwan Zend, 2010, photographer Indranil, copyright Indro Images

Yazdani Restaurant & bakery, Fort, 2010, photographer Bruce Carter, copyright Bruce Carter

Yazdani, Fort, Mumbai, 2010, photographer Anand Krishnamoorthi, copyright Anand Krishnamoorthi

Yazdani Restaurant & Bakery, Fort, 2021, photographer Bruce Carter, copyright Bruce Carter

Yazdani Restaurant & Bakery, Fort, 2021, photographer Bruce Carter, copyright Bruce Carter

Yazdani Bakery, 2016, photographer Chris Ilsley, copyright Chris Ilsley

Yazdani Restaurant & Bakery, Fort, 2021, photographer Bruce Carter, copyright Bruce Carter

Yazdani exterior 2021, artist Ashwin Tahiliani, copyright ATLASkeeda

Yazdani, Fort, Mumbai, 2006, photographer Akshay Mahajan, copyright Akshay Mahajan

Sunlight Restaurant & Stores

{Kalbadevi, Est. 1932}

For my grandfather and then my father, this was his home, this was his business, this was his everything…we will go too, one day. There’s nothing more to it than that.

PHEROZE JAMASPI, May 2008

________________________________

I’m Pheroze Beheram Irani - actually Jamaspi is the real family name. My grandfather Merwan started this place, and my father Beheram and his brothers came also from Yazd, Iran, and they made a life in India here at Sunlight.

My father had come illegally from Iran, in those days, I don’t know, you could do it I mean even now there are those ships, you know, with unregistered migrants. So, yaar, they had trouble in Iran, life was not easy. My grandfather started the business in early 1930s, my father and others came in early ‘40s. They had agricultural land but there was not enough water then to cultivate land in Yazd.

For my grandfather and then my father, this place became home, this was his business, this was his everything. I mean, you know, during those times we didn’t have to pay, we didn’t have to buy, this is a rented place, Ok. See, before the war, the landlords found it very difficult to get people to take their places on rent. They used to literally beg people – to run the show then pay them afterwards, pay the rent afterwards you know. The situation was that bad. They signed-into an agreement based on trust, you know, with the landlord. No money was involved, the rent was paid after they earned it. Rents were very, very cheap in Bombay back then.

My father and my uncles they used to sleep here, make a cushion and sleep here, on the first floor, sleep, work, run the business. Then they had a small place nearby, they would come and my mother used to cook food for them. They would wash here and sleep here only, they used to come to eat there. We didn’t sell any real food, we just had a provision store and tea at that time - tea, biscuits, bun maska, hard bread – brun, omelettes, just snack foods, that’s all.

So, they used to heat up the milk, that used to take them half an hour or more, in those vessels they’d heat up the milk, those tins that were also measures – one for sugar and also one for tea. So they had this big vessel you know and they used to heat the water and add the sugar and the tea so it was measured out properly. So they’d heat that, strain it and the tea was ready, They used to have those samovars you know like in Iran. And for that they had to get up very early, ‘cause the milkman used to come with the milk very early, then they had to get ready with the bun butter, get them ready and sort them ready for the first morning customers when they came early. The buildings opposite they used to be places for people, people who used to work on ships, especially people from Goa, to stay.

They’d sleep there, the lights used to go out by 8.30, 9 o’clock in those dormitories so they used to come here, read their books, write letters, have tea, chat with people, and go. That was at night. Morning they used to come for breakfast. But now, that has stopped, those people have gone from there now, that is all over. Finished.

During my school vacations my father and uncles used to make me come here and do things like fill up the glass jars, the burnies, I didn’t like to come here but I was forced to come and help. I mean, in those days there was no TV. There was just playing cricket, flying kites, doing marbles, innocent days and games. I’d have to leave my friends and come here and arrange those biscuits and sweets and then the provisions which used to come from the companies I had to sort them into small, medium, large size and weigh everything because my uncles were busy with customers so I would write down the price on each packet and arrange them, display them ready to sell. That was my work here as a kid. In the vacation. Not during school time. I used to hate it [laughs]. Then, when it became my livelihood, I liked it [laughing]. I began liking it. Never ever in my dreams I thought that I would have to come here. I was doing stenography, and I applied for a job and got it, but my father said don’t go there, come and work here, so I had to, to feed the family.

That was the early 1970s, my uncles, some went to Iran and other places, and the next generation, my generation, took over. Maharashtra started giving beer licenses, so we took up the beer license, which meant we had to get rid of the provision stores, anyway that was not very profitable, the beer business started being very profitable, so we continued with the beer then we took up the permit room, maybe after 10 years or so we took up the permit room. We remodelled the place. And that is the only reason we are still here.

See now, after myself, my brother, my cousin, there is no one to take up the shop. No way our kids would. So, this is the last. During my father’s time they would all be here all the partners at the one time. There was no sense of timing, of taking time off from work and enjoying life away from work you know. They were always tired. Why wouldn’t you be? This place, it is a small business, we were not like the Maharajas (laughs), but just like the Maharaja’s we will go too, one day. There’s nothing more to it than that.

_

From an interview with Pheroze Jamaspi, May 1, 2008

__________

IMAGES, top to bottom :

PHEROZE JAMASPI, Mumbai, 2020, photographer Bruce Carter, copyright Bruce Carter

JAMSHED JAMASPI, Sunlight Restaurant & Stores, Kalbadevi, ca. 1965, courtesy Pheroze Jamaspi

KALBADEVI, BOMBAY, ca. 1920, photographer unknown, courtesy Pheroze Jamaspi

JAMASPI BROTHERS, Bombay, ca. 1950, photographer unknown, courtesy Pheroze Jamaspi

JAMASPI BROTHERS, Kalbadevi, ca. 1955, photographer unknown, courtesy Pheroze Jamaspi

JAMASPI FAMILY members visiting Chak Chak, Iran, ca. 1968, photographer unknown, courtesy Pheroze Jamaspi

NOWRUZ, Persian New Year prayers, Sunlight Restaurant & Bar, Kalbadevi, March, 2017, photographer Bruce Carter, copyright Bruce Carter

PHEROZE JAMASPI, Bombay, ca. 1967, photographer unknown, courtesy Pheroze Jamaspi

SUNLIGHT RESTAURANT & BAR, Mumbai, 2019, photographer unknown

PHEROZE JAMASPI, 2020

JAMSHED JAMASPI, ca. 1965

KALBADEVI, BOMBAY, ca. 1920

JAMASPI BROTHERS, Bombay, ca. 1950

JAMASPI BROTHERS, ca. 1955

JAMASPI FAMILY members visiting Chak Chak, Iran, ca. 1968

NOWRUZ, Persian New Year prayers, Sunlight Restaurant & Bar, March, 2017

PHEROZE JAMASPI, ca. 1967

2020

2019